A tale of two horses

One rules Mongolia's frozen steppe. The other is still fighting to survive.

The first thing you notice driving across Mongolia's eastern steppe is the horses. They're everywhere – grazing in small herds, their winter coats and heavy eyelashes thick against the brutal cold. These aren't your typical domesticated horses. There's no barn to return to at night, no hay being trucked in. Even in temperatures that have my camera shutting down in protest, they're out here surviving just as their ancestors did thousands of years ago.

Mongolia's horses occupy a unique space between wild and tame. While they technically belong to local families, they live semi-feral lives, roaming freely across the steppe in herds of 15-50 animals led by a dominant stallion. They dig through snow for forage, defend themselves against wolves, and generally manage their own affairs with minimal human intervention.

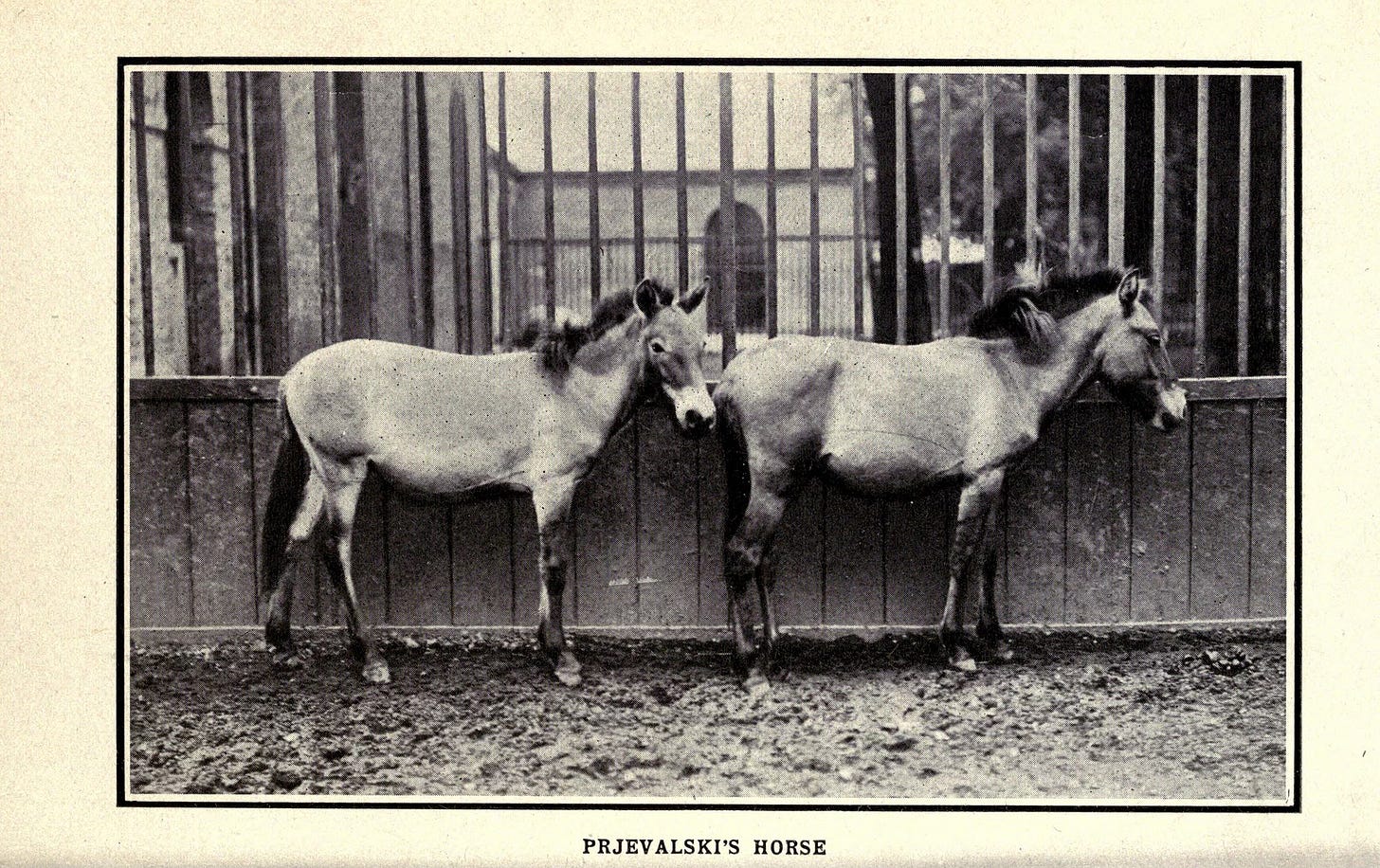

But there's another horse out here too – or at least, there used to be. The Przewalski's horse (pronounced "sheh-VAL-skee" and known locally as "takhi") is the world's last truly wild horse species. Unlike their semi-feral cousins, they were never domesticated. By 1969, hunting and habitat loss had driven them extinct in the wild.

The takhi's survival story is remarkable. All living Przewalski's horses descend from just 12 wild-caught ancestors and four domestic horses, creating what scientists call a genetic bottleneck. That's a bit like trying to rebuild humanity with just 16 people – you'd really want to make sure those folks weren't closely related.

The FUZZ Wednesday edition is paywalled, but it’s for the animals. 100% of your support goes directly to conservation causes you vote on each month. Become a paid subscriber to finish this article and contribute to worthy animal causes around the world, or we’ll see you Friday with more.

Through careful breeding programs and reintroduction efforts, there are now about 900 takhi living wild again, mostly in protected areas like Mongolia's Hustai National Park. They remain endangered, but they're slowly rebuilding their population.

What's fascinating is how these two horse populations share the landscape while maintaining distinct identities. They even have different numbers of chromosomes (33 pairs for takhi, 32 for domestic horses), though they can still produce fertile offspring if they meet – which is actually one of the biggest challenges for takhi conservation.

While I likely won't see any true takhi on this trip – they're typically concentrated in protected areas like Hustai National Park, hundreds of miles from where we're working – their semi-feral cousins are everywhere. And these domestic horses aren't just impressive survivors; they're central to life on the steppe. Families use every part of the horse: meat provides crucial protein during harsh winters, while fermented mare's milk (airag) serves both as a daily drink and plays an important role in ceremonial traditions. Even today, with Japanese motorcycles becoming increasingly common, horses remain essential for managing livestock across these vast distances.

This morning, watching a herd of Mongolian horses move across the frozen steppe, I couldn't help but marvel at their resilience. These horses survive temperatures from -45°F in winter to 110°F in summer, with no barns, no veterinary care, and no supplemental feed. Their wild cousins, the takhi, demonstrate that same hardiness, which makes their near-extinction and slow recovery all the more poignant.

Tomorrow, we head still deeper into the steppe to check some camera traps, hoping to spot some of the manuls we came here to find. But it's impossible not to be moved by these horses – both the abundant herds that still power daily life here, and their endangered wild relatives fighting their way back from the brink.

Quick Links! 🔗

A fascinating story in the New York Times this week profiles Tim Cernak, a pharmaceutical chemist who left his job at Merck to help save endangered species. The Gila monster's venom helped create blockbuster drugs like Ozempic, and now Cernak is trying to return the favor by developing medicines for sick reptiles. His first patient? A Gila monster named Pebbles fighting a potentially fatal parasite infection. It's a reminder that many of our most important medicines come from wildlife – all the more reason to protect these species before they disappear.

When UNC-Chapel Hill researchers noticed their captive loggerheads doing a little "food dance" – complete with flipper flaps and spins – they didn't just find it cute. They turned it into a breakthrough discovery about how sea turtles navigate. By watching when turtles performed their dance, scientists proved these reptiles can memorize the magnetic signatures of good feeding spots, essentially dropping pins in their internal GPS. It helps a bit toward explaining how they manage those incredible 10,000-mile migrations, though the exact mechanism remains a mystery.

The science of why some animals get saved (and others don't): A fascinating new study reveals how "cuteness" shapes conservation – sometimes with troubling results. I'm seeing this firsthand here too: while our January FUZZ Funds helped expand camera networks for the charismatic manul, my guide Vadim has spent years struggling to raise funds to continue his lifelong work on the Mongolian gazelle, despite the ungulates forming one of the last great animal migrations on Earth. It's a stark reminder that while all species deserve protection, some need a better PR team than others.

More from Mongolia…

Still no manul, and even the camera traps we're checking have only captured two images of cats so far. We're facing some challenges: Mongolia had a dzud — literally Mongolian for disaster — last year, one of the worst things that can happen to the steppe. I'll explain more on Friday, but essentially when winter brings too much snow, it buries the dried grass that free-ranging animals depend on for food, leading to mass die-offs. These events are becoming more frequent and intense.

Manuls aren't immune to the effects. During dzuds, their prey — pikas and other small rodents — struggle to access their burrows and food sources, leaving less food for the cats. Limited resources may force manuls to hunt during daylight hours, making them easier targets for the golden eagles that dominate these skies. Beyond the immediate survival challenges, it also means less reproductive success — fewer kittens born in summer, and fewer cats to photograph this winter.

Dzud aside, the lack of recent snowfall is making tracking difficult. While that's generally good news for the steppe, the existing snow has been hardened by weeks of wind and sun into a shell that barely breaks under my boots. A 10-pound cat hardly leaves a trace, making it nearly impossible to spot their movements, especially when they’re expert at blending themselves to like boulders.

I managed to glimpse a corsac fox, one of the manul's steppe neighbors. They're notoriously shy around humans – this one bolted as soon as our vehicle approached, but I still caught a decent shot from a distance.

One other cool animal we’ve seen a few times — the beautiful and opportunistic rough-legged buzzard.

Along eastern Mongolia's "highways" (for long stretches, just pothole-filled two-lane roads), buzzards have learned to use the sparse distance markers as hunting perches. They know vehicles create roadkill, especially among rodents crossing the asphalt. This one chose an abandoned tire pile as its lookout, waiting for cars to serve up an easy meal.

Even putting the lack of manul aside, this is a challenging trip. Though it’s beautiful driving, we’re covering massive distances — I’m to the north-east today, toward the China and Russia border — and we’re often logging these miles off road. The accommodations this time of year, though warm, often struggle on the toilet front — many of these tiny towns essentially empty out in summer as nomadic farmers head back onto the steppe, so investing in consistent indoor plumbing isn’t a priority.

It looks like I’ll get back into Ulaanbaatar on February 25, so I still have at least five solid days to catch a glimpse of the manul and learn from Vadim Kirilyuk’s experience with these animals. Wish me luck.

The information on the two horse species on the steppe was very interesting. Thank you! Stay warm out there.