America's most beautiful drive-through zoo?

Revisiting Edward Abbey's vision of Arches National Park.

By Dan Fletcher

First, a happy bit of housekeeping — It was a very close vote this month, but April’s FUZZ Funds donation of $264 is headed to the Wild Camel Protection Foundation for their work establishing a breeding center in the Gobi Desert for the world’s eighth most endangered mammal. I’ll round it up to an even $300 on your behalf, and we’ll look for additional ways to support their efforts in the future.

The Global Heritage Society, which works closely with the WCPF, actually just joined Substack, too — you can subscribe to their newsletter and stay connected to their work out in the Gobi.

Now, let's shift our focus from the Gobi Desert's camels to another arid landscape closer to home – the Colorado Plateau and Arches National Park.

Desert Solitaire no longer.

I'm headed back to Utah this weekend for the Moab Grand Fondo, a 50-mile tour through dusty desert roads on my bike. It’s primetime for Moab — ski season’s over in Colorado, the trails are too muddy for hiking up high, and the desert isn’t scorching just yet.

But one place I won't be going this time is Arches National Park. The park is also very much on the beaten path this time of year, which makes it a lot harder for an impromptu stop — there are timed entry slots and crowds at all the turnouts.

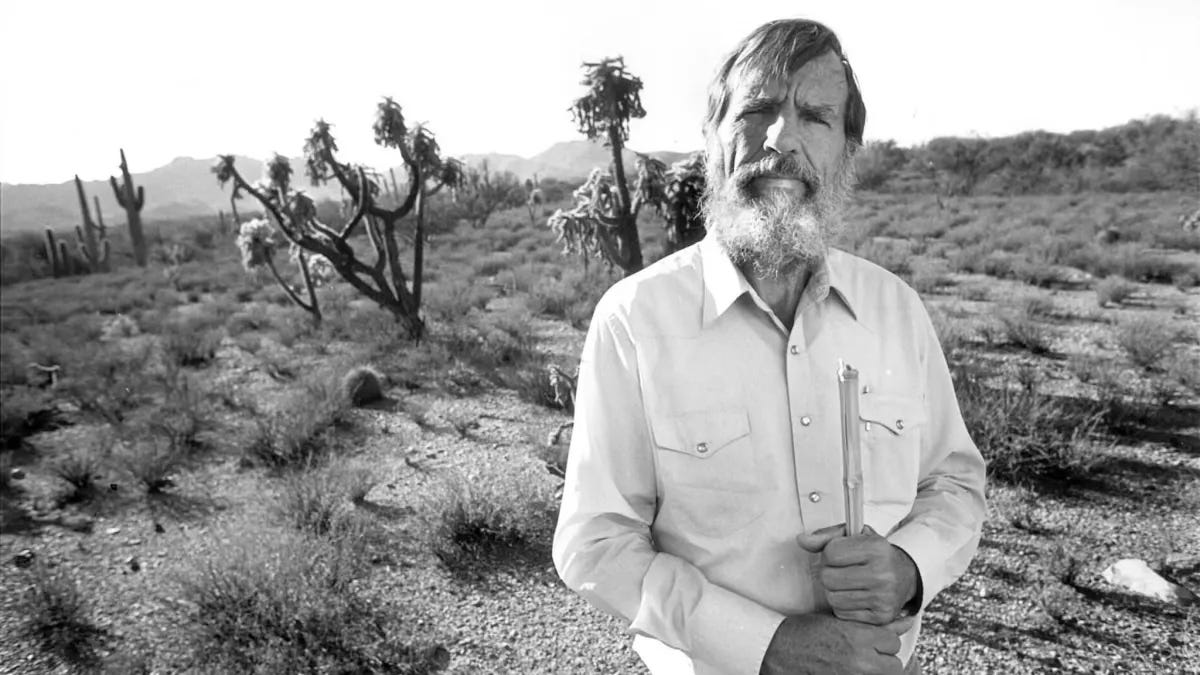

This is a very different park than the one in Edward Abbey's Desert Solitaire, which depicts his time alone as a ranger in the park in the summer of 1956 and 1957 when it was a national monument, in the very first days of infrastructure being built in Moab. I picked up a copy last week at Dinosaur National Monument, and I’ve been reading it to understand a bit more about wildlife management practices in the past, as well as how the National Park Service has evolved.

I always like the saying that the past may as well be a foreign country, and Abbey's book gives a sense of that. Far from the nearly 1.5 million people who visit Arches now each year, he usually encounters only a few weekend campers and sometimes no one at all. The transformation Abbey fears was merely beginning. As he documents the first paved roads cutting into the park, he mourns what would be lost — that authentic connection to a truly wild place.

It’s also worth reading for Abbey’s ecological insight during an era when the Park Service was actively working against predators rather than protecting them. His defense of bobcats, coyotes, and mountain lions as essential components of healthy ecosystems directly challenged the prevailing and wanton "control" programs of his day. While Arches has changed immeasurably, Abbey would likely be heartened by some changes today — predators are certainly treated with more kindness and respect, even if wildlife management isn't perfect.

Abbey was prescient on cattle, too. He calls livestock the "hoofed locust," blaming over-grazing for eroding soils, stripped cactus and vanished native grasses. His disgust is aimed as much at federal grazing leases as at the animals themselves — proof, he says, that land managers answer to ranchers, not ecosystems. That battle continues today across much of the West, particularly around issues like wolf reintroduction here in Colorado.

At the same time, it’s easy to find some faults with Abbey’s attitude, which comes off sometimes as a bit, well, exclusive. As I’ve written previously, the National Park Service has a dual mandate — preserving natural resources while providing for public enjoyment. The whole “providing for public enjoyment” bit tends to piss Abbey off, with his opposition to paved paths in the park to help the elderly or disabled, and his exhortation that many people would better off staying home. Sometimes it comes across as him saying that nature is for me, not for thee.

But that’s the fundamental paradox Abbey reckons with: officially "protected" places aren't necessarily truly wild. The very infrastructure that makes these landscapes accessible simultaneously diminishes their essential character. By building roads, parking lots and air-conditioned visitor centers, we fragment habitat, invite crowds and turn living deserts into drive-through zoos.

The Moab of today — with its mountain biking trails, adventure tourism, and crowded park shuttles — would be unrecognizable (and grotesque) to Abbey. Yet his fundamental concerns remain: How do we balance accessibility with preservation? Can we appreciate these landscapes without loving them to death?

For wildlife fans and conservationists, Abbey's book offers both inspiration and caution. He shows that seemingly "empty" country teems with life deserving protection. Development has left Arches protected, without being truly wild — a fate Abbey saw coming and railed against until his final days.

Quick link! 🔗

The animal holidays just keep coming: May 3 is International Leopard Day, and this shy and solitary cat is finding ways to survive alongside humans. While tigers grab headlines, leopards are quietly making history as urban pioneers, with thriving populations in cities like Mumbai where they prowl suburban parks between high-rises. These spotted cats can survive anywhere from dense rainforests to mountain peaks to city outskirts, but that flexibility hasn't made them invulnerable. Their global population has plummeted due to habitat loss and poaching (they're one of the most illegally traded animals worldwide), and in places like Bangladesh, they've vanished from 90% of their former range. Still, their urban success stories offer hope — if we can just give these resourceful cats room to roam, they seem ready to meet us halfway.

Have a great weekend!