The camera trap breakthrough that reads animal minds

Plus the butterflies that look identical, but are anything but.

By Dan Fletcher

Sorry I missed you all last week — we're deep in the edit for our first set of mini nature documentaries, and I didn't want to rush out a half-baked newsletter while buried in footage. The first film should be ready in the next couple weeks, along with a new brand launch focused specifically on national parks and nature. More on that soon.

But I couldn't wait any longer to share some good news: the Great Basin Institute won last month's FUZZ Funds vote. I just sent over $300 toward their programs to restore and educate people about the vast, weird stretch of America that exists in the rain shadow of the Sierras. It's the only place on Earth you'll find the Great Basin Bristlecone Pine — trees that can live over 4,000 years, making them among the oldest living things on the planet.

I think this marks the first time we've sent our monthly support toward a plant, though Great Basin National Park is far from just trees. The park hosts more than 300 species of mammals, birds and reptiles, seven of which exist nowhere else on Earth. It's a remarkable place that most people have never heard of, and one you'll get to see a lot more of in two weeks when our documentary premieres.

And now onto the news.

The breakthrough that turns every camera trap into a wildlife psychologist

Looking at camera trap photos from around the world, scientists face the same challenge everywhere: we can tell you a leopard walked past at 3:47 AM, but was it hunting? Stressed? Investigating a scent mark from another cat? The subtle behavioral cues that reveal what animals are actually thinking remain largely invisible to us.

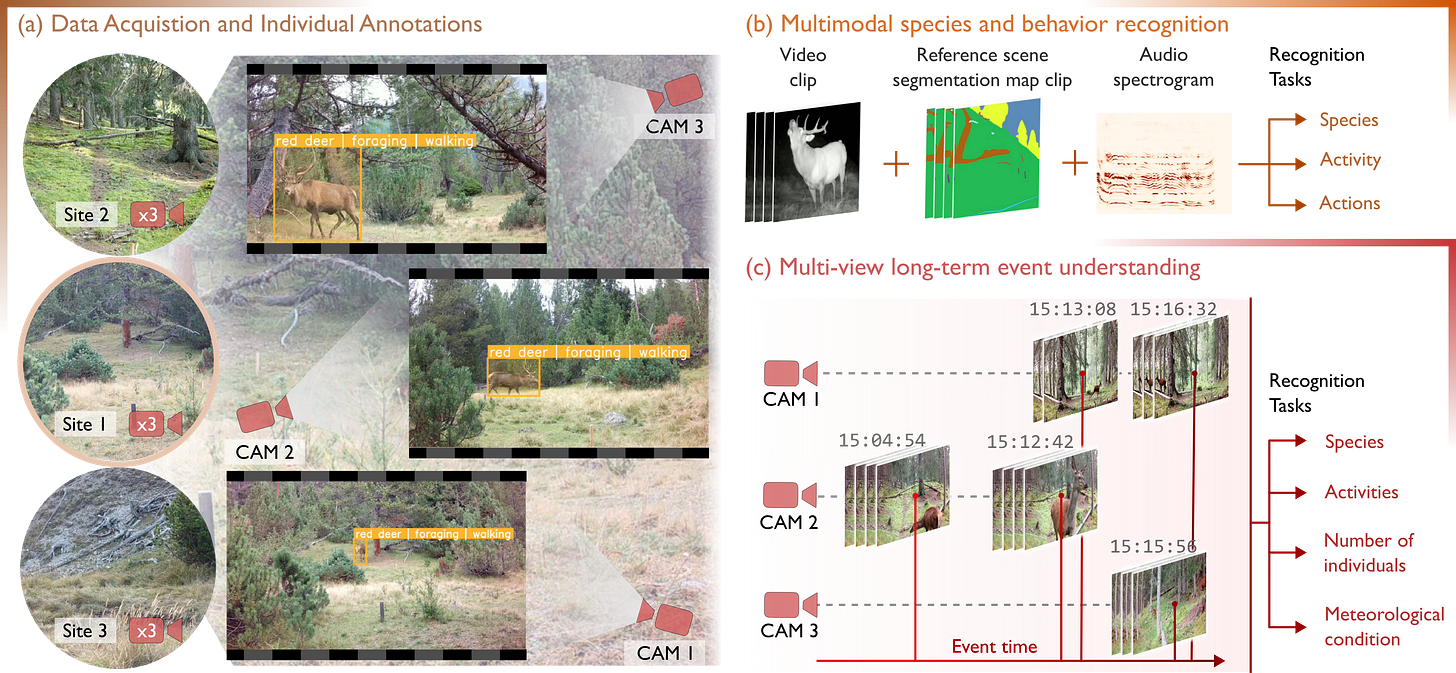

That's about to change, thanks to a breakthrough from Swiss researchers who've just created something that sounds like science fiction: an AI system that can watch wildlife footage and understand what animals are actually doing, not just that they're there.

The team at EPFL spent months in Switzerland's oldest national park, deploying nine camera traps across alpine meadows and forests to capture something unprecedented. Instead of the usual brief clips of animals triggering motion sensors, they recorded continuous footage—43 hours of raw video that they've transformed into the first dataset that can teach machines to interpret complex animal behavior.

They call it MammAlps, and it represents a fundamental shift in how we might monitor wildlife. Rather than simply counting animals or noting their presence, this system can distinguish between a deer casually browsing and one alert to predators, or identify the difference between a marmot's territorial display and its alarm call to the colony.

The technical achievement is impressive. They went beyond collecting video to generate detailed behavioral maps that combine multiple camera angles, audio recordings, and environmental context. When a red deer approaches a watering spot, the system doesn't just see "deer at water." It understands the approach behavior, drinking posture, and vigilance patterns that reveal the animal's internal state.

But the scalability of the approach makes it the most exciting for conservationists. Traditional wildlife behavior studies require researchers to spend months in the field, watching and interpreting animal actions. A single PhD student might analyze hundreds of hours of footage over years. This AI system could process that same amount of data in hours, recognizing behavioral patterns across thousands of camera trap locations simultaneously.

Imagine applying this technology to camera trap networks worldwide. Instead of just knowing that jaguars pass through a territory in the Amazon, scientists could understand their hunting strategies, stress levels, and social dynamics. They could identify when human activity is disrupting natural behaviors or track how climate change affects feeding patterns—all from the footage these remote cameras are already collecting.

The Swiss team has made their dataset freely available to researchers worldwide, recognizing that the real breakthrough comes when this technology spreads beyond any single research group. They're essentially providing the foundation for a new generation of wildlife monitoring tools that could transform how we understand and protect animal populations.

Of course, there are limitations. The system currently works best with larger mammals in relatively open environments—smaller, more elusive species might still prove challenging for even the most sophisticated AI. But as the technology develops, it promises to unlock secrets hidden in the millions of hours of wildlife footage collected every year by researchers, park managers, and conservation groups around the world.

Scientists are left wondering what camera trap images from tigers in India to snow leopards in Central Asia might reveal if we could truly understand the behavioral stories they contain. Perhaps that predator captured at 3:47 AM wasn't just passing through—maybe it was demonstrating hunting techniques that could help us understand how these species adapt to changing landscapes. The tools to decode those stories are finally within reach.

Quick links! 🔗

The scimitar-horned oryx just became one of the first large mammals to successfully come back from complete extinction in the wild. These elegant antelopes vanished entirely from their native Sahara in 2000, but over 600 now roam free across Chad's Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim reserve after one of conservation's most ambitious rescue efforts. The turnaround required 220 zoos worldwide to coordinate breeding programs for two decades, maintaining genetic diversity while scientists prepared release sites. Since 2016, more than 500 calves have been born in the wild, proving these desert specialists can reclaim their ancestral home.

Scientists discovered six new butterfly species that have been hiding in plain sight by looking exactly like each other. These glasswing butterflies from Central America appear identical to human eyes—and to predators who might want to eat them—but they use secret chemical "passwords" to find the right mates. It's like having six different people who all look like twins but can tell each other apart by smell. The butterflies evolved this clever strategy to stay safe from predators while still being able to reproduce with their own species. The discovery, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows how much biodiversity we're still missing even in well-studied regions, and demonstrates evolution's ingenuity in solving the problem of staying alive while finding love.

Awesome piece, really cool to think about what’s becoming possible in the realm of camera trap studies! Really looking forward to the docuseries!

Awesome! I'm glad automated analysis is being used in the wild. Now we can analyze animals other than ourselves and our lab mice.