The fish that live in a glowing hole in the desert

Plus, new research that makes me feel more and more like an orangutan

By Dan Fletcher

There's a hole in the Nevada desert, about an hour northwest of Las Vegas, where 47 fish live in what might be the strangest habitat on Earth. The opening is barely 20 feet across, but the water below glows an otherworldly blue and stays a constant 91 degrees year-round. Every single one of these fish was born on a limestone shelf the size of a conference table, 15 feet underwater.

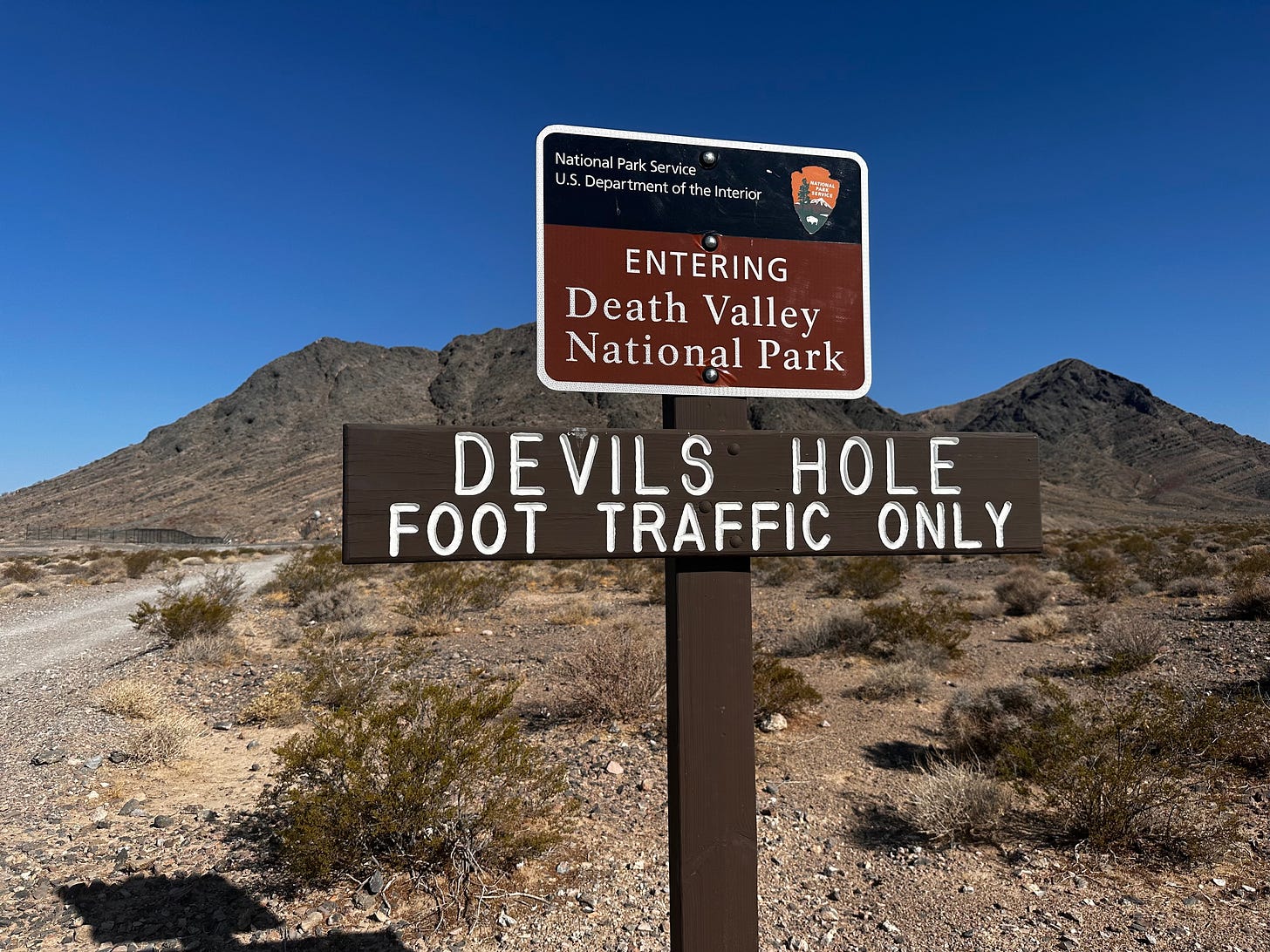

They're called Devil's Hole pupfish, and they shouldn't exist. This hole is a part of Death Valley—the hottest, driest place in North America. The nearest river is miles away. Yet these tiny fish have been making it work in this flooded cave since before humans built cities.

But perhaps most remarkably, in 1976, the fate of these fish went all the way to the Supreme Court. And the fish won.

The trouble started in 1968 when Nevada ranchers Francis and Marilyn Cappaert began pumping groundwater for their farming operation. They'd invested $7 million turning empty desert into productive farmland, employing 80 workers and following every water law on the books. By Nevada's rules, they owned the water beneath their land.

Except their pumping started draining Devil's Hole. For the first time in recorded history, water levels dropped. The shallow shelf where every pupfish had been born for hundreds of years was suddenly exposed to air. These fish had survived ice ages, but agriculture was about to wipe them out.

The legal battle was brutal. The government argued that when President Truman made Devil's Hole a national monument in 1952 — in large part due to the unique fish — he'd automatically reserved whatever water the fish needed to survive. The ranchers' lawyers said this would destroy western development—if the feds could claim water just by declaring land protected, every farm and city in the arid West was vulnerable.

Chief Justice Warren Burger delivered a unanimous decision: the fish would endure. Federal land reservations automatically include the water needed to fulfill their purpose, and these rights supersede state-approved claims. The Cappaerts lost their ranch. Forty-seven fish in a hole in the ground had reshaped American water law.

That was just the beginning of their problems, though. Population counts revealed something no biologist expected—wild swings from 500 fish down to a terrifying low of just 35 in 2013. Most populations that small simply disappear, but these fish kept bouncing back.

When scientists finally decoded their DNA in 2022, they found out why these fish shouldn't exist. The Devil's Hole pupfish showed the most extreme inbreeding ever documented in a wild vertebrate. The average fish shared 58% of its DNA with every other fish—equivalent to multiple generations of sibling breeding. They'd lost entire genes, including ones needed for their low-oxygen environment, yet somehow they keep reproducing.

Then earthquakes hit. A 7.0 quake in California last December created violent sloshing in Devil's Hole 500 miles away, washing eggs and larvae off their breeding shelf. A February quake repeated the damage. Spring counts revealed devastation: only 38 fish remained.

For the first time ever, scientists intervened directly. In May, they released 19 captive-bred pupfish into Devil's Hole—fish raised in a $4.5 million facility that perfectly replicates their impossible home. Today, 47 fish continue their ancient routines in water that glows like a portal to another world.

I was in Devil’s Hole last week working on a full video about this story—the Supreme Court drama, the genetic impossibilities, the conservation miracles. It's a tale that spans evolutionary history and legal precedent, proving that the loneliest species on Earth might have the most to teach us about survival. Look for it in a few weeks.

Back among the bristlecones

I’m writing this newsletter today from the Ancient Bristlecone Forest in California, part of the Inyo National Forest. We’re finishing up our bristlecone film by visiting the Schulman Grove, home to the Methuselah tree, the current oldest known living organism. But there’s rumors of another, even older tree that’s been lost to science due to an untimely death, a culture of secrecy and the protections necessary to save the oldest living things on earth.

More on that coming soon. But we also used it as an opportunity to do some night sky photography last night, since the lack of light pollution and high elevation make for some stunning views of the Milky Way.

Here’s the sky with a bristlecone that my friend Kyle and I found last night. It’s probably not the oldest living thing on earth, but who can say! It’s part of the mystery of this place.

Quick links! 🔗

Scientists discovered orangutans are just like us when they don't get enough sleep—they take power naps the next day to catch up. A 14-year study in Sumatra found that for every hour of nighttime sleep an orangutan loses, they nap an extra 10 minutes the following day. That's eerily similar to what sleep experts recommend for humans: short 5-15 minute power naps to restore mental performance. After my recent jet lag from Mongolia, I've never felt more kinship with our tree-dwelling cousins. The research also revealed that orangutans sleep poorly when others are nearby (relatable) and struggle to nap properly when it's too hot (extremely relatable). Unfortunately, rising temperatures from climate change could make it harder for these critically endangered apes to catch up on lost sleep—a problem that hits close to home for anyone who's ever tried to nap during a heat wave.

Scientists discovered a new species of ancient shark at Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, which feels like finding a penguin in the Sahara until you remember that 340 million years ago, Kentucky was underwater. The foot-long Macadens olsoni had curved teeth perfect for crushing mollusks in the warm, shallow sea that once covered what's now famous for limestone caves and bourbon distilleries. It's a perfect reminder that our planet's geography has been constantly reshuffling—today's underground cave systems were once teeming coral reefs. The discovery is part of a fossil bonanza at Mammoth Cave, where researchers have identified more than 40 different ancient shark species in just the past 10 months

I'm really glad humans intervened for the pupfish. When it comes to intervention, we should let common sense rather than purism drive us. Perhaps one day we will even populate another planet with Earth species, besides ourselves.