The largest land grab in American history

How a rushed Senate bill could auction off 258 million acres of critical wildlife habitat

By Dan Fletcher

Here’s today’s audio edition.

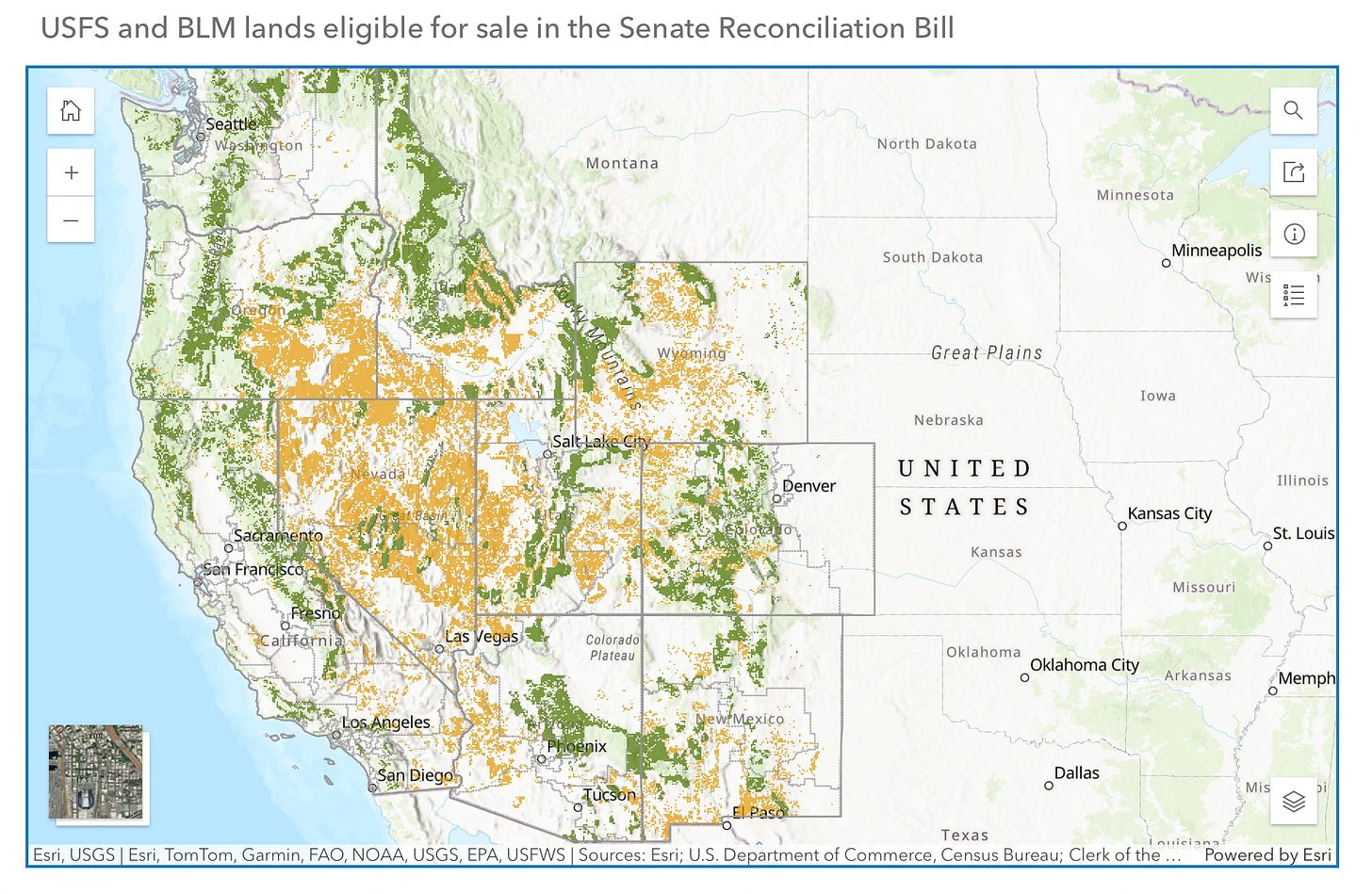

Picture an area larger than Texas and California combined. Now imagine putting all of it up for sale, with just 30 days' notice and no public hearings. That's essentially what Senator Mike Lee's budget reconciliation bill would do to America's public lands — forcing the sale of up to 3 million acres from a pool of 258 million eligible acres across the West.

The lands at risk aren't just empty desert. They include wilderness study areas, critical wildlife habitat, and the migration corridors that elk, bears, and countless other species have used for millennia. Breaking up these connected landscapes doesn't just reduce habitat — it fragments entire ecosystems in ways that can doom wildlife populations for generations.

Scientists have spent decades documenting why fragmenting connected landscapes is catastrophic for wildlife. When you break up large habitats into smaller, isolated patches, you don't just reduce available habitat — you fundamentally alter how ecosystems function. A 2015 study found that 70% of the world's forests now sit within one kilometer of a forest edge, subject to the degrading effects of fragmentation.

Consider an elk herd when development appears in their traditional migration route. These animals follow the same paths for generations, moving between summer alpine meadows and winter valleys. Break that corridor, and you force entire herds to find new routes — if they exist.

The bill's supporters claim they're targeting "underutilized" lands suitable for housing. But most of these 258 million acres sit nowhere near major population centers. In California alone, 16 million acres become eligible for sale, including areas adjacent to Yosemite, Mount Shasta, and Lake Tahoe. These aren't forgotten urban lots — they're intact ecosystems that hold the West's wildlife together.

Many of these areas were designated as critical wildlife habitat through a rigorous federal process under the Endangered Species Act. Scientists spend years identifying specific areas with the physical and biological features essential for species conservation. It’s a complicated mix, finding land with the right mix of denning sites, prey abundance, and connectivity. Selling off those acres doesn't just eliminate habitat; it can doom recovery efforts that taxpayers have funded for decades.

The timeline for this land grab is deliberately rushed. The bill demands agencies nominate tracts for sale within 30 days, then continue every 60 days until hitting arbitrary acreage targets. No public hearings, environmental assessments, or meaningful community consultation are required. (Montana’s also conspicuously excluded, for the simple reason that Lee needs the state’s two senators for this to have any chance of passing.)

This breakneck pace makes sense only if you're avoiding public scrutiny. When Americans learn their favorite hiking areas and hunting grounds are suddenly on the auction block, they get upset. The bill also sets up a bidding process favoring wealthy buyers over local communities. While state and local governments get "right of first refusal," most face budget shortfalls and can't compete with well-funded developers.

The bill's safeguards reveal its true priorities. National parks and official wilderness are exempt, as are lands with oil and gas leases, mining claims, and grazing permits. But areas set aside specifically for wildlife conservation can be sold to the highest bidder.

The economic analysis is dishonest too. These lands generate billions annually through recreation, hunting, fishing, and ecosystem services. The outdoor recreation economy alone contributes $1.2 trillion annually to the U.S. economy. Selling off the source of that economic activity for a one-time payment (estimated at $10-12 billion) is like selling your home to pay this month's rent.

Every western senator who claims to support hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation now faces a choice. They can stand with their constituents and the 90% of Americans who oppose selling public lands, or they can trade away irreplaceable wildlife habitat for some chump change and a pat on the back from developers.

The animals using these migration corridors don't get a vote. The elk don't understand state boundaries, and the lynx can't lobby for their survival. It's up to us to speak for them, and to remember that once these connections are broken, they can never be restored.

Quick links! 🔗

A haunting piece of footage from Senegal's Niokolo-Koba National Park shows what might be the country's last remaining elephant, captured on camera for the first time in five years. The solitary bull, nicknamed "Ousmane" after a park ranger, represents a heartbreaking endpoint to West Africa's elephant crisis — where hundreds once roamed this park, researchers now believe he may be completely alone. Ousmane is part of what conservationists call "ghost elephant" populations — tiny, isolated groups (often fewer than five individuals) scattered across West Africa that are too small to sustain themselves long-term. While his solitary appearance is sobering, Panthera and Senegal's park service are exploring whether they can bring in female elephants to establish a breeding population, potentially giving Ousmane — and Senegal's elephants — a fighting chance at survival.

And finally, sometimes the best conservation news comes from simply undoing past mistakes. California's northwestern pond turtle — the state's only native freshwater turtle — is making a remarkable comeback in Yosemite National Park after a seven-year effort to remove invasive American bullfrogs that had been devouring turtle hatchlings for decades. A UC Davis study published in Biological Conservation shows that where once only large adult turtles survived (too big for bullfrogs to eat), juvenile turtles are now thriving again. The recovery has created a ripple effect across the ecosystem: with bullfrog populations down, native frogs and salamanders are also returning to areas where their calls had been drowned out by the invasive species' notorious honking. It's a reminder that targeted removal of invasive species can sometimes restore natural balance more effectively than complex intervention programs.