The world's most trafficked mammal has another problem — it's delicious

Apparently. We never want to find out.

By Dan Fletcher

Here is today’s audio edition!

We’ve talked a lot about the usual conservation challenges — habitat loss, climate change, human-wildlife conflict. But sometimes, the biggest threat to an endangered species is simply that humans find it irresistibly tasty.

New research from Nigeria's Cross River National Park reveals a troubling reality for pangolins: among all the meats consumed in this biodiversity hotspot, pangolin meat scored significantly higher in palatability than almost every other option. In fact, the study found that while most wild meat can be potentially substituted with domestic meat, fish, or invertebrates based on taste alone, pangolins stood apart — only rodents could match their culinary appeal.

In other words, if you're trying to convince people to stop eating pangolins because something else tastes just as good... you're all but out of luck.

This comes from a new paper published in Conservation Biology, which examined meat preferences across 570 hunters, vendors, and household members who scored the palatability of 96 different animal species. And it’s a finding that's a serious problem for these remarkable scaly mammals, which are already the most trafficked wild animal on the planet. The eight pangolin species — four in Africa and four in Asia — face a devastating combination of threats, making them among the most endangered mammals on Earth.

Part of what makes this such a challenge is the extraordinary global scope of the pangolin trade. Their scales, made of the same material as your fingernails, are highly valued in traditional medicine across parts of Asia despite having no proven medicinal benefit. Meanwhile, their meat is considered a delicacy in regions spanning from West Africa to Vietnam.

The numbers are brutal: over 1 million pangolins (a low-end estimate) were poached between 2000 and 2019. Three species (the Chinese pangolin, Philippine pangolin, and Sunda pangolin) are now critically endangered, with populations of some having decreased by more than 80% in just three decades.

But while international trade in all pangolin species has been banned since 2016, the findings from this new study highlight the complexity of addressing local consumption patterns. The researchers discovered that while there's potential to substitute other types of meat for most wild species, pangolins present a unique challenge.

One surprising recommendation? The study suggests that high-breeding rodents like greater cane rats could potentially serve as a more sustainable substitute, as they were the only animal group with comparable palatability scores.

This brings up a thorny ethical question, though — should conservation organizations actually promote farming rodents as pangolin substitutes? In Nigeria, this approach is complicated by the fact that African brush-tailed porcupines, one of the most palatable rodent species, are actually legally protected themselves.

The situation reminds us that successful conservation isn't just about creating protected areas or passing laws — it's about understanding deeply human factors like taste preferences, cultural practices, and economic realities. And sometimes, the simple fact that something is delicious creates an extraordinarily difficult challenge for those working to save a species.

As the lead researcher Charles Emogor puts it: "Despite the potential for wild meat substitution, interventions aimed at promoting alternative protein must address other factors associated with wild meat consumption, including the cost and availability of alternatives and the cultural significance of wild meat."

For pangolins, their savory flavor is yet another obstacle in their fight for survival — but understanding this challenge is the first step toward developing more effective conservation approaches that might finally give these ancient, remarkable animals a fighting chance.

Quick links! 🔗

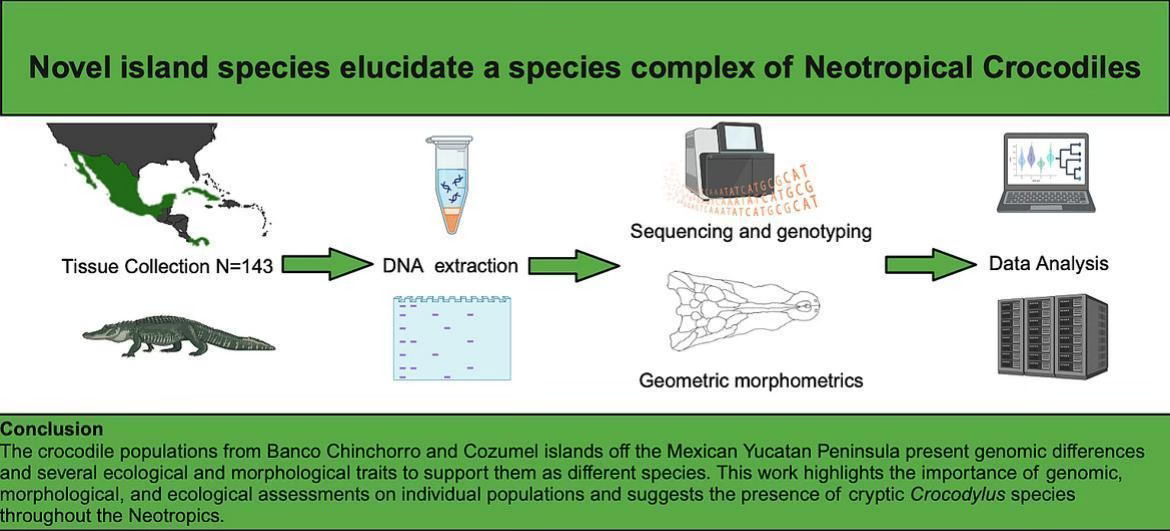

Scientists have discovered two previously unknown species of crocodile living on remote Caribbean islands off Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula. A new genetic study revealed that crocodiles on the island of Cozumel and the atoll of Banco Chinchorro — previously thought to be American crocodiles — are actually unique species in their own right. "The study is the first to extensively explore genomic and anatomical variation in these animals," says lead researcher Hans Larsson to the BBC. "It turns out there's a lot more diversity than we thought." Both new species number fewer than 1,000 breeding individuals and face threats from coastal development, highlighting the importance of identifying distinct species before they disappear.

Wildlife experts are "very excited" about the potential return of elk to Britain's landscape for the first time since the Neolithic era. A small grant will help begin feasibility studies on reintroducing these "keystone species" that once roamed freely throughout the UK. "They are one of our lost species," says Janice Bradley from Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust. "They would have roamed through the wetlands of the Trent, in and out of reed beds and pools, woods and grasslands." The project would initially keep elk in enclosures alongside recently reintroduced beavers, with long-term hopes of establishing populations along the Trent valley. Standing up to 2.1m (6ft 11in) at the shoulder and weighing up to 700kg, these massive animals could play a crucial role in maintaining wetland habitats for diverse other species.