When saving a rhino's life means changing who they are

The tough math of rhino dehorning

By Dan Fletcher

Here is today’s audio edition! And a programming note — no FUZZ on Monday/Wednesday of next week for a mini summer vacation. I’ll be taking a float down the Yampa, the west’s last free-flowing river, through Dinosaur National Monument. See you in a week.

I thought back to my conversations with Mark Kaptein as I read some new research on rhino dehorning. You met him in a March newsletter — the Dutch conservationist who spends nine months a year removing poaching snares from a South African reserve, watching the animals he's grown to know individually fall victim to an endless stream of wire traps. He's also the guy who casually mentioned helping with rhino dehorning operations, a detail that stuck with me long after our conversations in Estonia's forests.

This week, a new study published in Science put hard numbers on something Kaptein has witnessed firsthand: dehorning works, dramatically. Across eight South African reserves, removing rhino horns before poachers could get to them reduced killings by 78 percent over seven years. That's not a small improvement — that's the difference between watching a species slide toward extinction and buying crucial time for populations to recover.

The study shows a tactic that is desperate but effective. Researchers found that a horned rhino faces a 13 percent annual risk of being poached, while a dehorned rhino's risk drops to just 0.6 percent. Between 70 and 134 rhinos were saved from poaching in the 12 months following dehorning procedures. The intervention cost just over one percent of the reserves' $74 million anti-poaching budget, making it far more cost-effective than round-the-clock patrols or surveillance systems.

But those statistics tell only half the story. The deeper question, as lead researcher Timothy Kuiper puts it, is whether "a rhino still a rhino without its horns?" It turns out the answer is more complicated than conservationists initially hoped.

Additional research reveals that dehorning fundamentally changes how rhinos experience their world, particularly black rhinos. After losing their horns, these animals shrink their territories dramatically — on average, their home ranges contract by 45 percent. They also become 37 percent less likely to engage in social encounters, especially the crucial male-to-male interactions that establish dominance hierarchies and determine access to mates.

These aren't minor adjustments. They represent a fundamental shift in how black rhinos navigate their landscape and relate to each other. The horn isn't just an ornament or weapon — it's integral to their identity as a species. Without it, they become more cautious, more withdrawn, operating in a smaller world with fewer social connections.

White rhinos appear more resilient to the change, showing minimal alterations in their daily routines and social behaviors. The difference likely stems from their lifestyles: white rhinos are grazers who don't rely heavily on their horns for foraging, while black rhinos are browsers who use their horns to break branches and access foliage. Remove that tool, and you've altered their relationship with their environment in ways we're still trying to understand.

The behavioral changes raise difficult questions about what we're willing to sacrifice in the name of conservation. Ecologist Vanessa Duthé, who studies these effects, notes that while the behavioral modifications are measurable, they haven't yet translated into reduced population growth rates. The changes are "generally considered acceptable when weighed against the significant reduction in poaching," she told the Washington Post.

That calculation — acceptable behavioral changes versus prevented deaths — represents conservation in the 21st century. It's the kind of impossible choice that keep conservationists up at night, even as they recognize it as necessary. As one conservationist put it, "a live rhino without a horn is a lot better than a dead rhino without a horn."

The practice is expanding across southern and eastern Africa as reserves confront an unwinnable war against poaching syndicates. Even the success comes with caveats — some poachers have begun killing dehorned rhinos for their regrowing stumps, and more than 100 previously dehorned rhinos were still poached during the study period, some just weeks after the procedure. Kaptein told me frustrated poachers would sometimes kill a dehorned rhino to make sure they don’t waste time tracking it again.

So dehorning isn't a silver bullet, but it's bought time for a species teetering on the edge. Whether that time will be enough for larger solutions — addressing demand for rhino horn, dismantling criminal networks, developing alternative livelihoods for potential poachers — remains to be seen. For now, conservationists are making the hard choice to alter what it means to be a rhino in order to ensure rhinos exist at all.

It's the kind of pragmatic, heartbreaking decision that defines modern conservation work. And it's exactly the kind of impossible choice that people like Kaptein face every day in the field, knowing that the perfect solution doesn't exist, but that doing something imperfect is better than doing nothing at all.

Quick links! 🔗

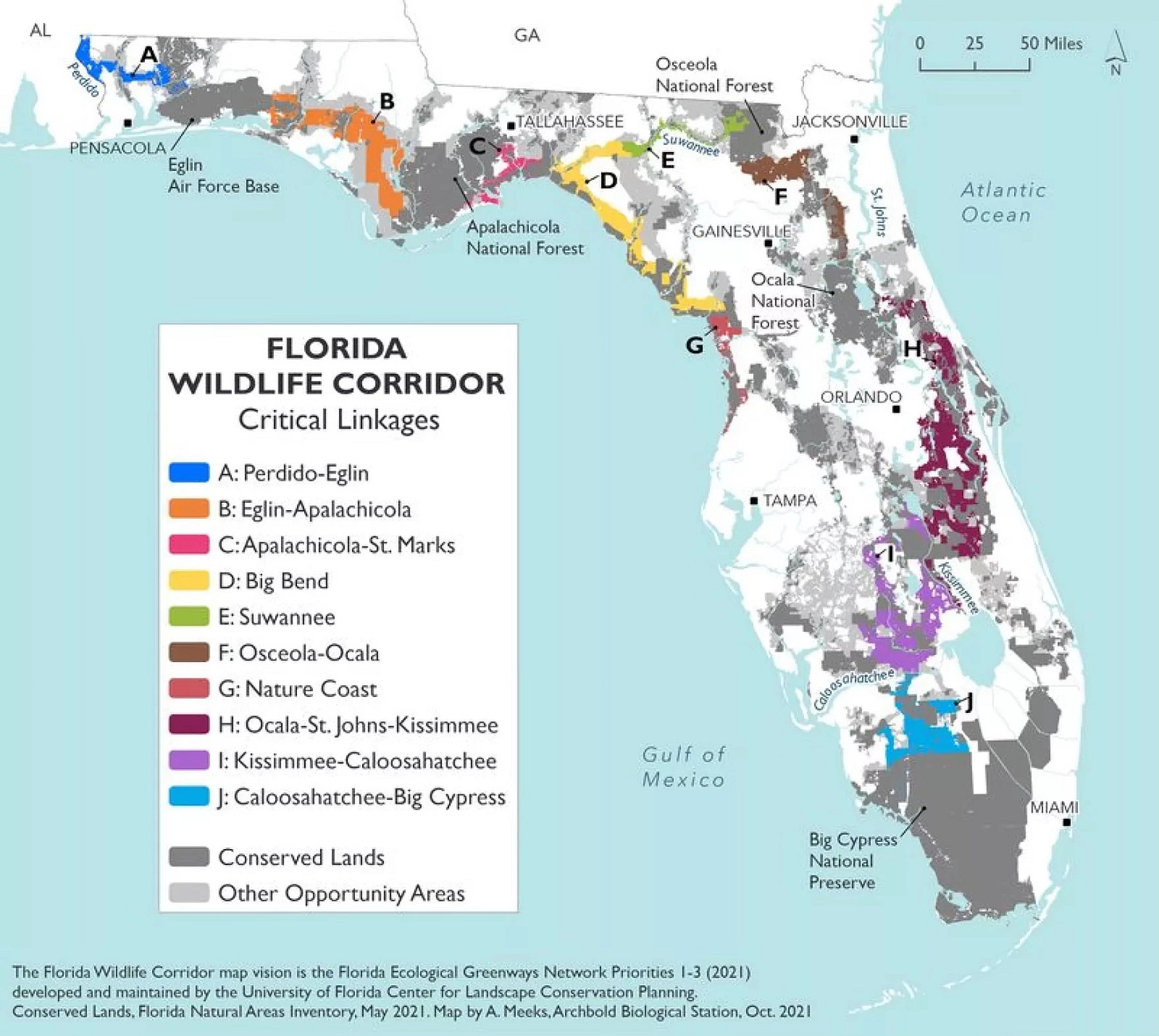

Disney World just dropped $1 million on one of Florida's most ambitious conservation projects — creating an 18-million-acre wildlife corridor spanning the entire state. The grant to the Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation will help close critical gaps between existing protected areas, turning what conservationists call "biological islands" into a connected network where wildlife can actually move and thrive. About half the targeted corridor already exists through purchases and conservation easements, but the trickiest pieces remain: those crucial bottleneck areas that connect everything together. The funding will support "Mind the Gaps" workshops where local stakeholders pore over maps to identify pinch points and brainstorm solutions. It's exactly the kind of landscape-scale thinking that Florida's endangered species desperately need — from the panthers we've covered extensively to the countless other animals squeezed by the state's relentless development.

And finally, National Geographic covers the aftermath of a terrorist attack that shattered one of Africa's most promising conservation success stories. On April 29, ISIS-linked insurgents stormed Mozambique's Niassa Special Reserve, killing eight people and forcing thousands to flee what had been a 17,000-square-mile sanctuary where wildlife and humans thrived together. The reserve was home to one of only seven lion populations exceeding 800 animals, plus 350 endangered African wild dogs and recovering elephant herds. Unlike typical "fortress conservation" that displaces local communities, Niassa's 70,000 residents in 47 villages were integral partners in protecting the wildlife — their deep connection to the land made them its best guardians. Now half the reserve sits abandoned under military occupation, tourism has collapsed, and the people who spent generations coexisting with lions and elephants are fleeing for their lives. Conservation ecologist Colleen Begg, whose Mariri Environmental Centre was targeted in the attack, lost team members but refuses to abandon two decades of work: "The only antidote to extremism is to keep going with conservation." Heartbreaking.