When saving chimpanzees means making them sick

Plus, the mysterious shoe-stealing foxes of Grand Teton National Park

By Dan Fletcher

Here is today’s audio edition!

It's World Chimpanzee Day, and I want to tell you about one of conservation's most troubling paradoxes. The very thing that's keeping our closest evolutionary relatives from extinction might also be killing them, one common cold at a time.

Picture this: You're trekking through Uganda's Kibale National Park, and you spot a family of chimpanzees just 20 feet away. A mother grooms her infant while juveniles swing overhead, completely unbothered by your presence. It's magical — the kind of encounter that transforms tourists into conservationists and funds the protection of entire ecosystems.

But here's what you can't see: the respiratory virus you're carrying from your international flight, harmless to you but potentially lethal to every chimpanzee in that forest.

Over the past 35 years at Kibale, nearly 60% of chimpanzee deaths have been traced to human pathogens — common colds, flu viruses, and other respiratory infections that barely make us sniffle but prove devastating to our evolutionary cousins. In 2016, a human metapneumovirus outbreak killed 25 of 205 chimpanzees at the park's Ngogo site, a 12% mortality rate from what would be a common cold in humans.

And that’s the problem. The diseases killing chimpanzees aren't exotic tropical pathogens — they're the mundane viruses we carry in our throats and lungs every day. When researchers genetically analyzed the respiratory syncytial virus that killed chimpanzees at Kibale, they found it was identical to strains circulating in the nearest human village. The viral outbreak at Taï National Park in 2016 also came from tourists. Even the common cold virus that infected 56 chimpanzees at Ngogo could be traced directly back to human contact.

What makes this especially insidious is that we often don't even know we're carrying these killers. A 2024 study revealed that while human children show symptoms when infected, adults humans become asymptomatic carriers — making the temperature checks and health screenings at park entrances essentially useless for preventing transmission.

But here’s the paradox: the tourism and research that brings these diseases are some of the only things standing between chimpanzees and total extinction.

Chimpanzee tourism generates extraordinary conservation benefits across Africa. In Uganda alone, it accounts for 52% of all tourism revenue. At Rwanda's parks, tourism contributed over 70% of foreign exchange earnings for a decade. This money translates directly into anti-poaching patrols, habitat restoration, and community development projects that give local people alternatives to hunting.

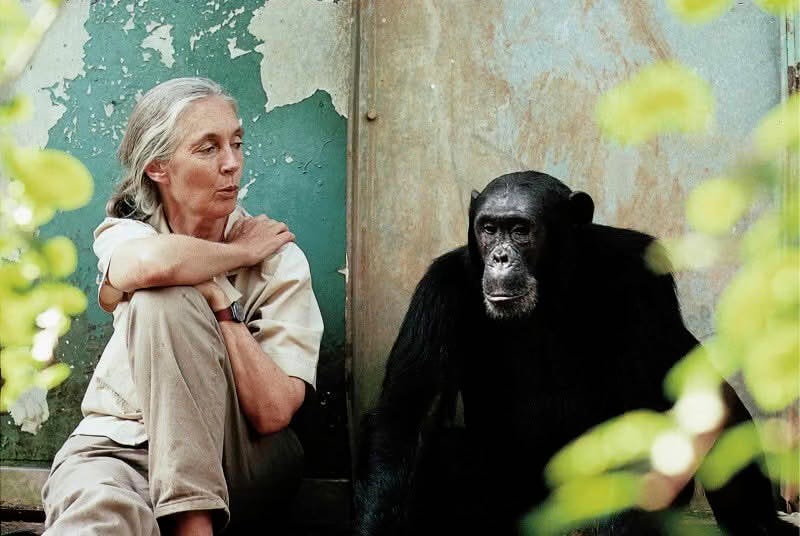

The protective effect goes beyond economics. At Gombe, where Jane Goodall began the world's longest-running chimpanzee study 65 years ago, constant human presence has kept poachers at bay. The simple fact that tourists and researchers are watching creates a deterrent effect that's proven more effective than any fence.

Only 150,000 to 340,000 chimpanzees remain in the wild today, down from as many as a million a century ago. Western chimpanzees have crashed by 80% in just 25 years. Without the revenue and protection that human contact provides, most remaining populations would likely disappear within decades.

So we're stuck with an impossible choice: engage with chimpanzees and risk making them sick, or leave them alone and watch them get poached into extinction.

The COVID-19 pandemic offered an unexpected opportunity to test ways around this paradox. Despite sharing identical ACE2 receptors with humans — making them highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 — no wild chimpanzee that we know of contracted COVID-19. But this success came at enormous cost: complete tourism shutdowns devastated conservation funding while proving that strict biosecurity actually works.

Research sites rapidly adapted with enhanced protocols that would have seemed absurd pre-pandemic. Mandatory 14-day quarantines for international visitors. Distance requirements increased from 7 to 30 feet. Universal masking, daily health checks, reduced group sizes. But it worked — at Kibale's Ngogo site, coughing rates in chimpanzees dropped from 1.73% to just 0.075% after implementing these measures.

The results suggest a path forward that doesn't require choosing between contact and isolation. Rwanda's Gishwati Forest showcases what's possible — the chimpanzee population increased 130% from just 13 individuals in 2008 to 30 today through a combination of strict health protocols, high-end tourism, and deep community engagement.

But maintaining these protocols requires constant vigilance and significant costs. Quarantine facilities, health monitoring systems, and reduced group sizes all eat into the revenue that makes conservation possible. It's a delicate balance that becomes harder to maintain as tourism pressure increases and budgets tighten.

Tourism has ramped back up across Africa after pandemic shutdowns. The protocols that kept chimpanzees COVID-free are being relaxed as economic pressures mount. Whether we maintain the hard-won gains in disease prevention or slide back into old habits may determine whether future generations get to meet our evolutionary cousins in the wild, or only read about them in history books.

Quick links! 🔗

More monkey business for today: Scientists just discovered that long-tailed macaques have surprisingly human-like viewing preferences when watching videos. In a study at a Dutch research center, 28 macaques consistently chose to watch footage of fights over grooming, running, or sitting around — and they paid extra attention when the videos featured monkeys they actually knew rather than strangers. Lower-ranking, less dominant monkeys were the most engaged viewers, possibly because they need to stay alert to potential threats. The findings suggest our fascination with conflict and familiar faces in media might be an evolutionary trait we share with our primate relatives — making monkey movie nights not so different from our own.

Grand Teton National Park rangers are dealing with an unexpected problem: foxes have stolen 32 shoes from campers, and the situation is getting worse because visitors are now deliberately leaving footwear outside their tents hoping to catch a glimpse of the "cute" thieves. What started as 19 missing shoes prompted park signs asking people to secure their footwear, but instead of solving the problem, it backfired spectacularly. Rangers posted a humorous PSA reminding visitors that while the behavior seems adorable, teaching wildlife to associate humans with opportunity can lead to the animals being relocated or euthanized. Nobody knows why the foxes want the shoes, but park officials are clear that feeding this habit isn't helping anyone — especially not the foxes.

We would protect our cats and dogs if we knew we could give them our deadly diseases, so the same should be done for our chimpanzees cousins in the wild.